It has been a whipsaw year in the oil market as the war in Ukraine, the uneven Covid recovery, rising interest rates and an Opec+ output cut continue to create uncertainty about what comes next. Looking ahead to 2023, the emerging consensus seems to be that, despite an impending recession, prices will strengthen based on the Opec+ decision, sanctions against Russia and unintended consequences of the oil price cap.

Bullish forecasts are further reinforced by the perception that structural underinvestment is constraining supply. But the widespread market narrative that supply is in jeopardy is largely driven by news headlines, not the fundamentals.

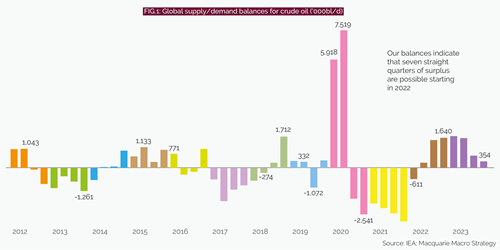

A deeper look at the data tells a very different story. From hourly labour utilisation, plans for new projects offshore and a resilient supply chain, our analysis indicates the four quarters of 2023 will be part of the seven-quarter-long supply surplus (see Fig.1).

Overstated

Many bullish views, particularly in relation to the Opec+ production cut, are pinned to circular drivers. The bigger signal of the policy decision has been lost in the excitement; as with previous Opec+ decisions, the move is a sign that the market is oversupplied structurally. Large surpluses were in progress even without maximalist Opec+ production or the full impact of 2022 US production growth, and amid unusually large supply disruptions globally.

Regarding Russia, it is unlikely that Western sanctions or the price cap will have the impact on supply that the market fears, given Russia’s share of overall output and the likely workarounds it will engineer. Government officials now realise that Russia and many buyers can circumvent the price cap plan with their own ships and services, with news agency Reuters in late October quoting a US Treasury official saying it is not unreasonable to estimate that 80–90pc of Russian oil will continue to flow outside the cap mechanism.

A third concern, which in our view is unfounded, is the belief that the market will experience a supply shock when the US government decides to refill the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). The SPR is still a massively large reserve, and refills do not need to happen all at once. The most likely scenario is a gradual replenishment that will have minimal impact on the market.

Deep dive

A deeper look at industry metrics shows that we are facing global surpluses, not deficits, and that is likely to continue through the end of 2023—most notably in Q1 and Q2. For example, the US tight oil rig count is now up by 30pc year-to-date, according to oil services firm Baker Hughes and Macquarie Macro Strategy.

We estimate 2022 and 2023 exit production growth will realise at 1.2mn bl/d and 0.8mn bl/d respectively, both significantly above consensus. We estimate oil production per rig year for a shale rig in the Midland basin of the Permian has increased to c.10,000bl/d in 2022 from roughly 6,000bl/d in 2017. Similarly, average 90-day productivity in the New Mexico region of the Delaware basin has increased from 750bl/d in 2018 to c.1,000bl/d in 2021, data from intelligence firm S&P Global and Macquarie Macro Strategy show.

And labour utilisation is up in line with production, meaning the industry is working more hours than in January 2020, according to our analysis based on data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Looking ahead, the global long-lead pipeline—evaluated on the basis of plans for new offshore project startups—is strong. Our analysis indicates planned projects each year through to 2025 are on average greater than any year from 2010 to 2018. Although the supply chain is tight, it is responding; consider steel imports, which are now exceeding pre-pandemic levels, according to federal trade agency USITC.

Looking at the current E&P situation from a historical perspective, the recovery from the Covid decline in rig counts is strong. The upward trajectory is similar to historical recovery curves in 2008–09 and 2014–16 (see Fig.2).

Despite lower total capex, overall productivity is rising due to improved technology, automation and the desire by oil companies to streamline projects, in some cases reducing the breakeven point by as much as 30pc, according to Macquarie Macro Strategy analysis. Offshore producers are far more efficient at finding and drilling for oil, and shale E&P is benefitting from greater horsepower speed and high-grading. Overall, companies are reducing unnecessary customisation and taking the opportunity to reuse existing infrastructure to keep costs in check.

We are surprised at the level of misunderstanding on the underinvestment theme; our analysis indicates that investment has been more than adequate when adjusted for productivity.

Where underinvestment is occurring

While investment is steady upstream, it is the downstream side of the equation where will and interest are lacking. The US has less than half the number of refineries it had in 1985, and across the country more than 20 refineries have shut down since 2020, according to the EIA and S&P Global.

Shutdowns and a lack of new investment are occurring for a variety of reasons. When demand for fuel dropped sharply during Covid lockdowns, plants that distilled crude into gasoline, diesel and jet fuel shut down and companies postponed upgrades. At the same time, many refineries needing maintenance or repairs because of age, fires or storm damage shuttered permanently amid rising costs and projections for reduced demand tied to the transition to cleaner energy; closures of older facilities with high emissions also gained points for optics.

For companies to invest in new or upgraded refineries to process crude, the capital outlay must make economic sense. The design and production of a new refinery, with expected utilisation for three or four decades, can cost as much as $10bn and take 4–6 years, according to data provider Bloomberg.

Under current market conditions and looking ahead to future demand scenarios, the numbers simply do not add up as more and more large energy customers make net-zero commitments. Neither oil companies nor potential investors want to be stuck with a capital-intensive refining asset in a falling demand market, and this puts a big chill on new investment.

Oil majors, refiners and even bargain-hunting private equity investors will struggle to make the case to buy existing refineries, especially when considering changing winds that favour lower-carbon alternatives to their output. Upgrades and expansions underway will help capacity growth, but not enough to bring capacity back to pre-pandemic production.

Some companies are converting refineries to renewable diesel to gain tax benefits from investing in fuels with lower-carbon emissions. For example, US refiner Phillips 66 will convert the Rodeo refinery in the San Francisco Bay area into one of the largest renewable fuels plants in the world. The refinery aims to produce 800mn gal/yr of renewable diesel, gasoline and jet fuel from feedstocks such as used cooking oil, fats, greases and soybean oil.

Back in June, Chevron CEO Mike Wirth said he believes there will never be another new refinery built in the US. “You are looking at committing capital ten years out that will need decades to offer a return for shareholders, in a policy environment where governments around the world are saying: ‘We do not want these products’,” he told Bloomberg TV.

Reasons to be bullish?

It is clear that refinery output is what it is. For now, and into 2023 at least, the data says crude production is in better shape than people think. Looking ahead, the larger question is how policymakers will take a measured approach to avoid underproducing fossil fuels while the world is transitioning.

As countries wean themselves off hydrocarbons, they need to consider how, when and why they direct incentives towards old and new energy production to ensure a smooth transition—in normal times and to ensure resilience during disruptive events such as military conflicts, pandemics and severe weather.

Looking ahead to the next decade, transition is and will continue to occur, and market forces will in time find their balance. Expect Opec+ to keep cutting production, and do not be surprised if we end up with $30/bl oil by 2032.

Vikas Dwivedi is global oil and gas strategist for financial services group Macquarie.

This article is part of the upcoming special report Outlook 2023, which features expectations from the energy industry for key trends in the year ahead. Sign up here to receive updates about the full report.

Comments