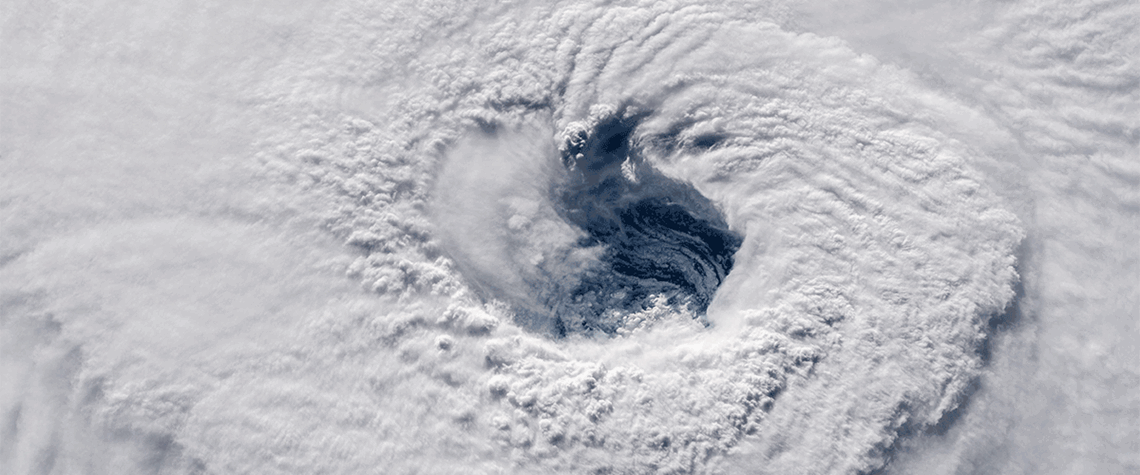

Amid the violence of a hurricane, the eye of the storm offers some temporary respite. This is perhaps a good analogy of where we are with global gas and LNG markets.

With LNG spot and European gas prices having surged to more than $70/mn Btu (equivalent to more than $400/bl) earlier this year, international LNG prices have now fallen by 50pc, to c.$30/mn Btu. While this is good news for gas consumers, it would be wrong to think the global gas crisis is over.

The seeds of the current crisis were planted well before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The buildout of Australian and US LNG in the mid-to-late 2010s precipitated a global glut of LNG supply by the end of the decade. It was only recently, in the summer of 2020, that LNG prices touched historic lows of $2/mn Btu, threatening the viability of many projects.

Gas market oversupply, coupled with decline in investment in oil and gas projects by global oil majors, has resulted in a scarcity of new LNG projects coming to the market, which will not end anytime soon. This comes at a time when the Russian invasion of Ukraine has removed 80pc of Russian exports to Europe, or c.120bn m³/yr of supply, creating a gaping chasm in global gas supply that is not easily filled.

Price cure

Extreme shortages of gas in Europe have so far been prevented by record gas prices, which have pulled available LNG cargoes into Europe—amounting to c.50bn m³—and the replacement of gas with coal in Asia, which has resulted in sharply lower gas imports and the first year of negative gas demand growth in China in living memory. The ability to rebuild gas inventories to normal levels ahead of the winter heating season has likely averted a serious gas crisis in Europe this winter and resulted in the pullback of gas and LNG prices.

But the outlook for 2023 still looks worrying for gas buyers. As gas inventories are depleted over the coming winter months, the question is how to restock them for winter 2023–24. The Nord Stream 1 pipeline was only shut down in September—a full year’s absence makes next year far more precarious from the supply side. Unless Europe has an exceptionally mild winter and exits the season with swollen gas inventories, next year’s supply-demand deficit could be materially larger. Moreover, with very little (<10mn t/yr) of new liquefaction capacity coming online next year or even in 2024, there is no LNG cavalry riding to the rescue in the imminent future.

Twin drivers

Aside from global economic growth, two factors will shape the outlook for gas markets in 2023. The first is the Russia-Ukraine war. Continuation of the conflict will result in gas supply to Europe being significantly curtailed for next year.

While this is most likely the base case, we believe there are grounds for optimism. The war is clearly not going well on the ground for Russia, and it is possible it could end next year. Whether Europe would agree to buy gas from Russia after the cessation of the conflict is not clear, notwithstanding the damage to Nord Stream 1.

We assume that Europe, with few other options in the short term, will have to be pragmatic and that gas would flow again from Russia to Europe, albeit at reduced volumes. The hesitancy of European utilities to buy long-term, 20-year LNG from either the US or Qatar in significant volumes might also suggest a belief that Russian supply could come back at some point.

The second factor is whether China emerges from its zero-Covid policies and starts to demand higher quantities of energy. In 2022, China’s LNG imports declined by an unprecedented 20pc. This was partly due to high European prices, which diverted spot LNG cargoes from Asia back into the Atlantic basin, but it was also due to a collapse in industrial demand in China.

If China lifts its zero-Covid policies and industrial demand starts to grow, then it will start to compete with Europe for additional LNG cargoes. Already, we have seen the Chinese government ban the resale of LNG cargoes heading into this winter, which could exacerbate the LNG supply crunch if extended into the new year.

From our optimistic perspective, we believe an end to the Russia-Ukraine war and an end to China’s zero-Covid policies will take place sometime in 2023. However, if the conflict does not end until later in the year, it could still result in another significant uptick in gas and LNG prices as buyers in Europe fret about the possibility of gas supply shortages for winter 2023–24. As such, we believe that gas and LNG prices could remain elevated for much of 2023 and another upcycle is likely.

Planting seeds

But this will not last forever. Gas and LNG has been and will always be a highly cyclical market. An end to the Russia-Ukraine war could result in the resumption of some Russian gas flows into Europe by 2024. By 2025, a new wave of LNG will reach the market as Qatar, Canada and the US start up new liquefaction projects, providing relief to markets.

What the longer-term repercussions of the Russian invasion of Ukraine mean for gas markets remains to be seen, but there are some key conclusions. Firstly, we will mostly likely need more rather than fewer LNG projects. The US and Qatar look well placed.

Secondly, Russia will have to pivot towards the east. While Europe may choose to reduce its dependence on Russian gas, China and India will become critical end-markets for oil, gas and LNG.

Finally, energy security will play a far greater role than it has in the past. For most of the world, the volatility in LNG prices will likely promote a faster push away from fossil fuels and into low-carbon energy—solar, wind, hydrogen and lithium-ion batteries. This will take time, but the seeds of this new shift in energy are being planted.

Neil Beveridge is the senior oil analyst at Sanford C Bernstein.

This article is part of our special Outlook 2023 report, which features predictions and expectations from the energy industry on key trends in the year ahead. Click here to read the full report.

Comments