It has been a year of seismic change in the context of the global energy transition. The conflict in Ukraine has exposed an overreliance on a small number of traditional fuel producers and a distinct lack of (green) alternatives to fall back on. And all the while, our planet continues to warm at a worrying pace.

It has been a wake-up call: the world needs to fast-track the move to cleaner fuels.

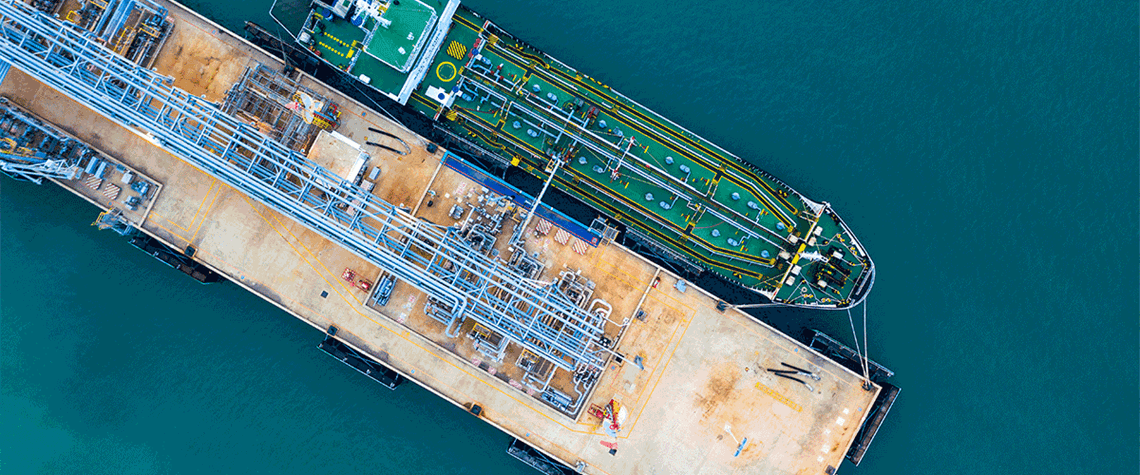

But for this to become a reality, the right infrastructure needs to be in place to support the production and transportation of those fuels. This will require cross-sectoral collaboration on a scale we have rarely seen to date, and the shipping industry will have to play its part. After all, shipping is a vital cog in the global energy transition, with up to 50pc of the green fuels of the future set to be moved by sea.

At Cop27 in Sharm el-Sheikh in November, we saw shipping play an increasing role in bringing together various sectors and organisations. The Green Shipping Challenge event, hosted by the US State Department and the prime minister of Norway, and attended by US climate envoy John Kerry among others, comprised more than 40 major announcements relating to green shipping solutions and initiatives.

I am proud that shipping is taking these proactive steps as an enabler of the wider energy transition, but we need to bring everyone else along with us. A successful transition will only be achieved in unison with the other relevant sectors.

For this reason, an announcement that was particularly well received at Cop27 was Norway, Panama and Uruguay joining Canada and the UAE in the growing Clean Energy Marine Hubs (CEMH) initiative. CEMH, which is co-led by a taskforce of CEOs, is a public-private initiative aiming to accelerate the production, export and import of low-carbon fuels across the world. It is a great example of collaboration between shipping, ports and policymakers. The initiative is not about decarbonising the shipping industry, it is far more holistic than that. It has been set up to facilitate the global energy transition.

Green fuel inaction

Despite progress in some areas, inaction around green fuel production remains our greatest enemy. Currently, governments are missing a trick. It is all well and good announcing green shipping corridors, but what is the point if there is no green fuel—such as hydrogen and bioenergy—to transport? A new report, authored by Manchester University’s Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, was published at Cop27 and shone a light on this very issue.

It found that governments need to urgently strengthen and expand their low-carbon fuel policies to give hydrogen producers, shippers, and consumers the confidence they need to invest. Without this, we will struggle to scale up the production of green fuels sufficiently to meet Paris climate goals.

According to the IEA, the world needs 50–150mn t of low-carbon hydrogen by 2030, but current projects will produce only 24mn t. Furthermore, only 4pc of current national hydrogen infrastructure projects have moved from concept to final-stage funding. Clearly, there is a worrying gap between what is required and what is currently being done.

The Tyndall Centre report found that the transport of ammonia and bioenergy by sea in the coming decades could match shipments of gas and coal today. But this would need around 20 large new ammonia carriers to be built every year, and the industry has yet to see the clear market signals required to give them confidence to invest and build at this scale.

While the global energy transition is littered with complexities and obstacles, we must not forget the huge economic opportunity it presents. For instance, countries in the Global South, particularly coastal ones, have bountiful renewable energy resources amounting to 10,000TWh of production potential. With immediate investment, they would be able to significantly increase production, and proactive policymakers would enjoy the advantages associated with being first movers.

The year 2022 was a turbulent one for global climate and energy security. There will no doubt be more challenges in 2023 and beyond, but if governments can recognise the unprecedented opportunity that the energy transition can offer, we will see a huge collaborative leap forward that sets the world on a firmer path to decarbonisation.

Guy Platten is the secretary general at the International Chamber of Shipping.

This article is part of our special Outlook 2023 report, which features predictions and expectations from the energy industry on key trends in the year ahead. Click here to read the full report.

Comments